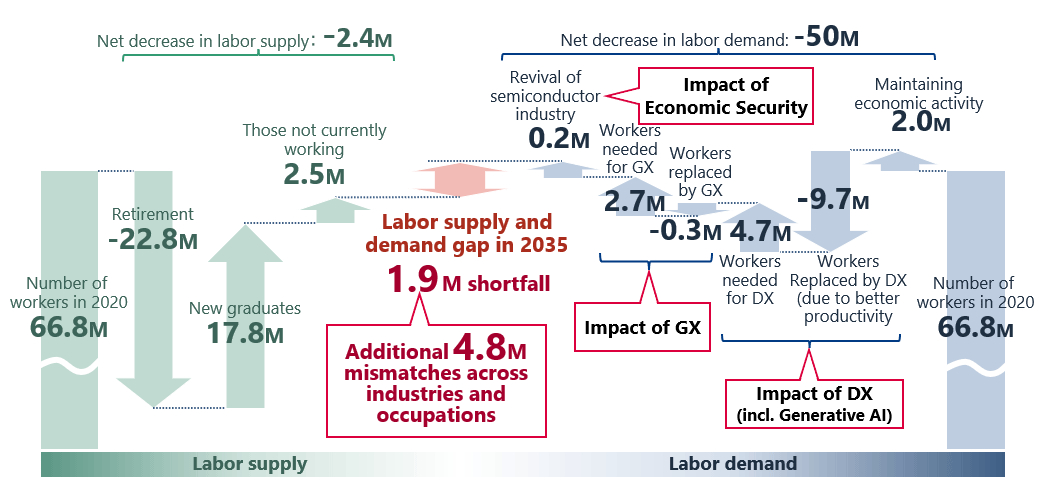

First, industrial structure transformation will generate new labor demand of equivalent quantity as the employment that is lost. As shown in Figure 1, the digital transformation, the green transformation, and revitalization of the semiconductor industry will add demand for 4.7 million, 2.7 million, and 0.2 million workers each. However, the gap between labor supply and demand will be approximately 1.9 million, because labor supply will be reduced by population decline.

Second, the skills mismatch will pose a greater problem than the labor shortage. A large number of professional technical jobs will be created, mainly in IT. Meanwhile, most reduction will occur in clerical service and sales jobs. We calculated that the skills-to-jobs mismatch will give rise to a shortage of 4.8 million workers, far greater than the labor shortage of 1.9 million workers.

This means that if we are to harness digital technologies and achieve carbon neutrality, we must somehow fill a labor shortage of 6.7 million workers in a few decades. A mismatch of this size can only be rectified by large-scale reskilling and encouraging labor mobility within and between companies.

Third, the mismatch also arises in units of tasks and skills rather than people or jobs. Based on the above calculations, digital transformation, including greater use of generative AI, will reduce labor demand by around 9.7 million workers, roughly 15% of our forecast for employed persons in 2035.

The key point here is that advancing digital technologies will not simply replace the 9.7 million jobs lost; they will replace a portion of the tasks that a given job comprises. Naturally, a certain task may be included in many different jobs. We must also be aware that generative AI, like ChatGPT, may take over from humans some non-routine tasks* previously thought beyond the realm of machines.

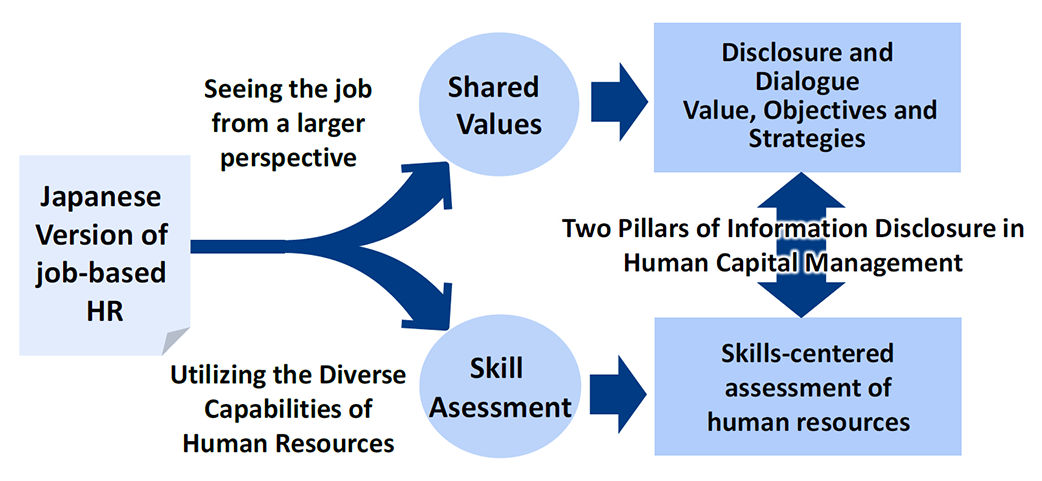

Japan will face an increasingly constrained labor supply and should regard task replacement by generative AI and other technologies as a big opportunity to improve productivity, not a threat. We must determine in all occupations which human tasks can be taken over by machines, identify which human skills enable us to utilize AI to its fullest power, and refine those skills.

One example is the skill of asking ChatGPT appropriate questions, making proper decisions based on the information thus obtained, and bringing team members on board to put decisions into action. Companies and governments must clearly delineate skills like these and encourage the workforce to master them.

These three points hint at imminent transformation to the structure of our industries depending on how we deal with economic security and transformations both digital and green. This will set into motion human resource movement beyond individual companies and redefine the skills in demand across a broad range of occupations. It is essential that the government is aware of these shifts while advancing its three-pronged set of labor market reforms.