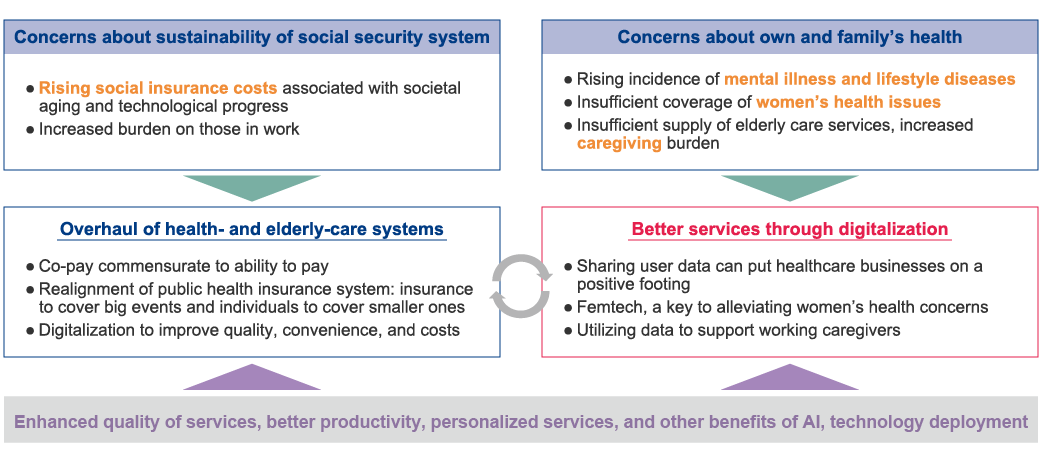

Japanese who are in their working age worry most that the healthcare and pensions systems are souring the country's solvency.

This is the segment's top answer when it comes to concerns related to society from our survey of 30,000 Japanese residents, topping the list for 12 years running, ever since we started measuring in 2011. And just as the media often report, expenditures for healthcare and taking care of the elderly are skyrocketing, resulting in higher social-insurance contributions for the actively employed: over the past 20 years, health insurance contributions have risen by almost a third for those working. And the low birthrate means fewer people will be around to share the costs, so their contributions are bound to continue rising.

The human-resources aspect looks dire too: there is an increasingly acute shortage of people to fill nursing, care-giving, and other frontline jobs that keep healthcare and elderly-care services running. Many institutions have to juggle the few personnel they have effectively enough to ensure the wellbeing of the patients and resident in their care. If the situation continues unaddressed, it could become unsustainable, threatening the viability of the whole social security system.

This is the segment's top answer when it comes to concerns related to society from our survey of 30,000 Japanese residents, topping the list for 12 years running, ever since we started measuring in 2011. And just as the media often report, expenditures for healthcare and taking care of the elderly are skyrocketing, resulting in higher social-insurance contributions for the actively employed: over the past 20 years, health insurance contributions have risen by almost a third for those working. And the low birthrate means fewer people will be around to share the costs, so their contributions are bound to continue rising.

The human-resources aspect looks dire too: there is an increasingly acute shortage of people to fill nursing, care-giving, and other frontline jobs that keep healthcare and elderly-care services running. Many institutions have to juggle the few personnel they have effectively enough to ensure the wellbeing of the patients and resident in their care. If the situation continues unaddressed, it could become unsustainable, threatening the viability of the whole social security system.