The global economy in 2024 will probably experience a slowdown in growth due to three constraints. These stem from actions taken to deal with high uncertainty. We forecast growth to underrun potential growth rates in the US, China, and the eurozone.

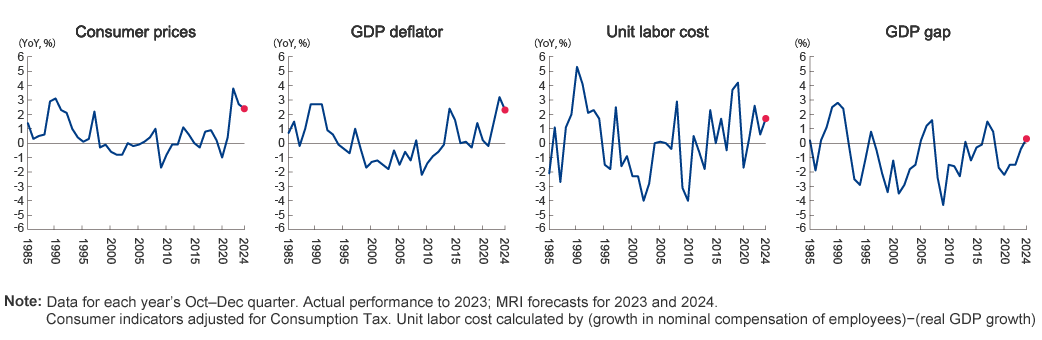

The first constraint is the process of reigning in inflation. Inflation can directly provoke popular ire, and getting a rein on it tends to be a high political priority. In the US, many voters cite inflation as their reason for not supporting the Biden administration. Though the recent wave of global inflation finally peaked out during the first half of 2023, inflation still outstrips targets by several percentage points in many countries.

This is due to internal factors: lingering upward pressure on prices kept strong by the likes of expected inflation and wage increases driven by labor shortage. Central banks in the US and Europe will probably keep interest rates high through the first half of 2024 to get persistent inflation down. This will act as a drag on internal demand.

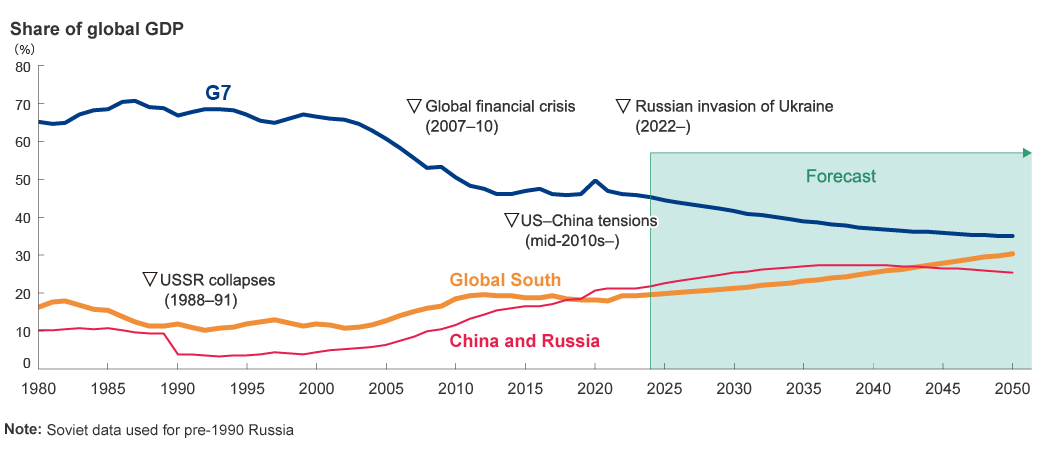

The second constraint on growth is the risk of supply chain disruptions. To avoid the effects of economic blackmail by rival countries and risk of loss due to transport network chaos, many countries are turning to “friendshoring,” the practice of building networks with suppliers in neighboring or friendly countries. And parallel to this, ensuring stable energy supply is also essential for decarbonization. Although these trends are positive for the economy inasmuch as they encourage more investment, the cost increases associated with rebuilding supply chains puts pressure on corporate profitability; so ultimately they could hit consumers in the pocketbook when the costs get passed on as higher prices, potentially acting as a downward pressure on the economy.

Debt marks the third constraint. In Europe and North America, rate hikes are likely to raise the cost of interest on debt. This will make it all the more urgent for governments to get debt they piled up during the pandemic under control. And among emerging economies, China has some particularly serious issues to deal with: non-financial private sector debt exceeded $40 trillion in 2023, surpassing that of the US to make China the country with the world’s highest. Even compared to its GDP per capita of about $20,000 (measured by purchasing power), this level is excessive, and the country is in a position that looks very similar to Japan’s when its bubble burst. As we see it, a slowdown in growth is inevitable.

Though the uncertainty will clear up somewhat if these three constraints can be kept at bay, there are also plenty of things that could rekindle further uncertainty about the road ahead. The spread of the Israel–Hamas conflagration to other parts of the Middle East is one. That could easily cause crude prices to spike or put a choke on supply. A closing of the Suez Canal, as happened in response to the Six Day War in 1967, would deal a massive blow to shipping worldwide. And critical elections are on the calendar this year in Taiwan, Indonesia, Russia, and India—not to mention the US presidential election in November. If Donald Trump returns to the White House, his America-first policies could result in the country’s retire from international cooperation and throw domestic decarbonization policies into reverse.